Aerobatic pilots take to sky over Pocahontas

-

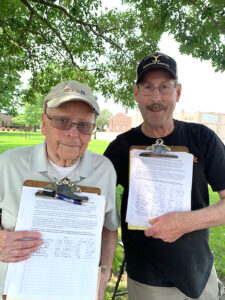

-Messenger photo by Joe Sutter

Aaron McCartan explains one of the keys to a successful stunt planeÑit’s very lightÑas he lifts his plane with one hand. McCartan will compete in this top of the line Panzl S-330 at the U.S. National Aerobatics Championships this weekends. Only 11 of this 2,000 pound, 330 horsepower plane have been made.

-

-Messenger photo by Joe Sutter

Cory Johnson prepares to take off in a Pitts biplane Wednesday. Biplanes and mono-wing planes can all compete at the highest levels of aerobatic competition. Four friends with three Pitts and a Panzl will take off today from Pocahontas to the National Championship at Oskosh, Wisconsin.

- -Messenger photo by Joe Sutter Cory Johnson takes off in a tiny Pitts aerobatic biplane, over this much larger parked Air Tractor crop duster and another Pitts at the Pocahontas Municipal Airport.

-

-Messenger photo by Joe Sutter

Aaron McCartan watches one of his fellow pilots perform a series of maneuvers while coach Linda Morrissey gives feedback over the radio. Morrissey was the 1992 Vice World Unlimited Champion aerobatics pilot, and runs one of the best stunt pilot training camps in the world according to McCartan.

- -Messenger photo by Joe Sutter Aaron McCartan takes off over the fields outside Pocahontas in a Panzl S-330 for the third day of training before the U.S. National Aerobatics Championships this weekend. McCartan, of Algona, and Brent Smith of St. Louis are hoping to do well enough to join the U.S. team at the International competition in Romania.

-

-Messenger photo by Joe Sutter

The cockpit of Aaron McCartan’s Panzl S-330 stunt plane is sparse, with nothing extra that could add weight. At center is the sheet listing every move required in McCartan’s upcoming run; points will be deducted for each maneuver not completed or not done well. The rear seat cushion is his parachute.

-

-Messenger photo by Joe Sutter

Aaron McCartan curves through a loop in a series of maneuvers during practice in his Panzl S-330.

-Messenger photo by Joe Sutter

Aaron McCartan explains one of the keys to a successful stunt planeÑit's very lightÑas he lifts his plane with one hand. McCartan will compete in this top of the line Panzl S-330 at the U.S. National Aerobatics Championships this weekends. Only 11 of this 2,000 pound, 330 horsepower plane have been made.

POCAHONTAS — The skies have been loud over Pocahontas this week.

Aaron McCartan, of Algona, and his team of aerobatic pilots have been putting in a full four days of training before they fly off to the U.S. National Aerobatic Championships in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, today.

McCartan’s ambitions this year are high — he and Brent Smith, of St. Louis, Missouri, hope to make it to the U.S. Advanced team which will fly in the world championships next year in Romania.

“I paused my Unlimited ambitions because this year we’re trying out for the United States Aerobatic team in Advanced,” McCartan said. “The top eight pilots in the nation. It’s a very small group.”

McCartan has brought home numerous awards and championships over the years, including U.S. Advanced championship in 2016. He hopes eventually to compete in the highest class, Unlimited, one step above Advanced in the five-level difficulty system.

-Messenger photo by Joe Sutter

Cory Johnson prepares to take off in a Pitts biplane Wednesday. Biplanes and mono-wing planes can all compete at the highest levels of aerobatic competition. Four friends with three Pitts and a Panzl will take off today from Pocahontas to the National Championship at Oskosh, Wisconsin.

“Unlimited is substantially more complicated than what I just demonstrated,” he said, landing after a tough advanced sequence Wednesday. “Thousands more maneuvers… Lots more rolling elements, lots more snaps. It’s very, very busy.”

His plane is built for “busy”. The Panzl S-330 single-wing plane is one of only 11 of its kind. It’s very powerful, very capable, and very safe, he said.

His three friends are flying different variations of Pitts Specials — biplanes.

“There is no right airplane,” said Justin Hickson, from the Twin Cities, who grew up in Sioux City. “Biplanes, monoplanes, each one has pros and cons. But when you get the right pilot…”

The Panzl is better in vertical maneuvers, while the biplanes can stay maneuverable at very low speeds.

-Messenger photo by Joe Sutter Cory Johnson takes off in a tiny Pitts aerobatic biplane, over this much larger parked Air Tractor crop duster and another Pitts at the Pocahontas Municipal Airport.

The Panzl only weighs around 1,200 pounds and has a 330 horsepower engine. When McCartan is performing his rolls and snaps he can experience g-forces of 8 positive gs, and 7 negative gs.

That puts extreme stress on the human body, McCartan said. Pilots only stay up for about 15 minutes when practicing.

“When you are competing at the advanced, just to maintain tolerance to the g-forces, and be safely proficient in the maneuvers, you have to fly two to three times during the week and once or twice on the weekend just to be safe and proficient,” McCartan said. “If you want to do really well you’re looking at three to four flights on the weekend, and three to four flights during the week. So you’re looking at flying almost every day if you want to compete at Advanced or Unlimited. And there’s a big skill set.”

Pilots get a sequence of maneuvers they have to complete, Hickson said. Multiple judges watch the plane and score pilots on how well they complete each move, taking away points if they skip a maneuver or add any.

Pilots have to stay above a minimum altitude — a ‘floor’ — which gets lower in more advanced classes. And this all has to be done within a “box” in the air just 3,300 feet by 3,300 feet, Hickson said.

-Messenger photo by Joe Sutter

Aaron McCartan watches one of his fellow pilots perform a series of maneuvers while coach Linda Morrissey gives feedback over the radio. Morrissey was the 1992 Vice World Unlimited Champion aerobatics pilot, and runs one of the best stunt pilot training camps in the world according to McCartan.

That may sound big if you had to walk it out, but a stunt plane going over 200 mph will make it to the other side of the box in 10 seconds, he said.

Hickson, McCartan, Smith and Cory Johnson, of Wisconsin, shared space this week with McCartan’s parents who have a hanger at the Pocahontas airport.

Their coach, critiquing every roll and loop, was Linda Morrissey, who runs an aerobatics training camp the group attends in Kansas.

“She and her husband run one of the best camps in the world,” McCartan said. “She was 1992 Vice World Unlimited Champion. She was second in the world.”

McCartan himself first got his wings because his parents were pilots also.

-Messenger photo by Joe Sutter Aaron McCartan takes off over the fields outside Pocahontas in a Panzl S-330 for the third day of training before the U.S. National Aerobatics Championships this weekend. McCartan, of Algona, and Brent Smith of St. Louis are hoping to do well enough to join the U.S. team at the International competition in Romania.

“Both of them flew aerobatics in a recreational sense,” he said. “Today we’re doing precision aerobatics, trying to demonstrate perfect maneuvers. My parents did it for the safety aspects, learning how to handle the aircraft at every attitude and being fully aware of what the aircraft can do.”

He’s been flying aerobatics for 10 years now, while Smith has been at it for 25 years.

“He is extremely experienced. Potentially one of my most fierce competitors,” McCartan said as Smith’s biplane rolled down the runway back to the hanger. “It has nothing to do with I have more performance. He has put the time in to get the most out of that airplane.”

The two spent the last few months sending “the dirtiest, nastiest maneuvers we could back and forth, trying to trip each other up, trying to push each other,” he said.

In the process they found one sequence that looks innocuous, but is incredibly difficult to pull off in the air.

-Messenger photo by Joe Sutter

The cockpit of Aaron McCartan's Panzl S-330 stunt plane is sparse, with nothing extra that could add weight. At center is the sheet listing every move required in McCartan's upcoming run; points will be deducted for each maneuver not completed or not done well. The rear seat cushion is his parachute.

“I went out and tried them, and the first one I did I had to abort the maneuver,” McCartan said. “I had to attack it completely different.”

And pilots each get to submit a maneuver that the judges may accept as part of the “unknown” sequence every competitor has to complete–a sequence they haven’t seen before.

Smith’s favorite involves a steep dive before a “half snap pull.”

“With the snap roll you have a max snap speed. In my aircraft its 130 miles per hour,” Smith said. “So you’re already at 100 mph when you start the push. If you don’t manage the push correctly you’ll be beyond the speed you can do the snap roll.”

“As soon as the nose starts coming down, the plane starts to accelerate. So you need to be able to manage that energy,” McCartan said.

“Energy management is key,” Smith said.

-Messenger photo by Joe Sutter

Aaron McCartan curves through a loop in a series of maneuvers during practice in his Panzl S-330.