An old train celebrates a new railroad

Canadian companies own 35% of Iowa's railroads.

-

-Messenger photo by Robert E. Oliver

On May 10, a special train arrived along downtown Davenport’s riverfront to commemorate one year since the merger of Canadian Pacific and Kansas City Southern Railways resulted in a new company — Canadian Pacific Kansas City. The railroad is the first, and only, line to connect all three major economies of North America: Canada, the USA and Mexico. An estimated 2,500 people turned out in spring weather to see the train, which was headed by a magnificently-restored 94-year-old steam locomotive.

-

-Messenger photo by Robert E. Oliver

Dustin Elliott, director of Facilities for Van Diest Supply Co., Webster City, manages the company’s shipments with Canadian National Railways. Receiving more than 700 railcars each year, the chemical manufacturer could not operate without reliable rail service.

-Messenger photo by Robert E. Oliver

On May 10, a special train arrived along downtown Davenport's riverfront to commemorate one year since the merger of Canadian Pacific and Kansas City Southern Railways resulted in a new company — Canadian Pacific Kansas City. The railroad is the first, and only, line to connect all three major economies of North America: Canada, the USA and Mexico. An estimated 2,500 people turned out in spring weather to see the train, which was headed by a magnificently-restored 94-year-old steam locomotive.

DAVENPORT — A Canadian Pacific passenger train made a three-hour stop in downtown Davenport on May 10.

Now you might well ask, what self-respecting passenger train would stop anywhere for three hours?

This was not just any passenger train. It originated in Calgary, Alberta, Canada, destined for Mexico City, running the entire distance over one railroad: the awkwardly-named Canadian Pacific Kansas City. The train commemorates the merger, a year ago, of two large railroads: Canadian Pacific and Kansas City Southern.

This train has a lot to tell us about the state of railroads in America, and Iowa, today.

The train was made up of vintage passenger cars, some more than 75 years old. While diesel locomotives provided the real pulling power, leading the train was C.P. Steam Locomotive No. 2816. Built in December 1930, in Montreal, it once hauled Canadian Pacific’s premier transcontinental passenger trains across the prairies, plains and mountains of that vast nation to the north. Canadian Pacific spent more than $2 million to restore the locomotive in its Calgary shops, a process that took two years.

-Messenger photo by Robert E. Oliver

Dustin Elliott, director of Facilities for Van Diest Supply Co., Webster City, manages the company's shipments with Canadian National Railways. Receiving more than 700 railcars each year, the chemical manufacturer could not operate without reliable rail service.

Why would a modern railroad choose such an old-fashioned symbol for its birthday party?

Probably because it remains the definitive, indelible image of a train in the minds of Americans. Throughout much of 2816’s working life, railroads hauled more than half the freight and 20% of passengers carried on the continent. Today, after more than 100 years of federally-funded highways and airports, railroads carry about 40% of long-distance freight, still more than any other mode. Most freight transported by rail today can’t be moved any other way.

Bottom line: Railroads remain essential, even vital, to the nation’s economy and security.

It may be the ultimate message C.P. No. 2816, a 94-year-old steam engine, has for us today is that the inherent advantages of moving both goods and people by such an efficient, safe and “green” means — by train — is as modern as this minute. It’s something every American instinctively knew 60 years ago, but may be a new idea to younger generations of Americans.

Are you, reader, surprised that a Canadian company owns and operates a railroad in the United States?

You may be, but it’s an old idea. Back in 1888 (no, this isn’t an error), Canadian Pacific bought a 50% interest in the Minneapolis & Sault St. Marie railroad, popularly known as the Soo Line, the phonetic spelling of the French name Sault. The acquisition gave C.P. access to the Twin Cities and Chicago, then and now the center of the U.S. railway network.

Not to be outdone, Canadian Pacific’s archrival — Canadian National Railways — bought control of the little-known Duluth, Winnipeg & Pacific in 1918, bringing it into Duluth, Minnesota, a key Great Lakes port and gateway to the Mesabi Range, which still supplies iron ore to U.S. and Canadian steel makers. Later, in 1923, C.B. bought the Grand Trunk Western Railway, putting it into Detroit and Chicago. This was the status quo for decades.

In November 1995, after more than 70 years of public ownership, Canadian National was privatized. Many of the initial investors were American. The newly-invigorated C.N. then went on a U.S. buying spree that’s still going on today.

First, it acquired Illinois Central in 1998, then Wisconsin Central in 2001, giving it a direct line across Wisconsin to Chicago.

In 2012, C.N. added the Elgin, Joliet & Eastern to its network. Little-known to the public, this 164-mile long “belt line” connects virtually every railroad in Chicago with every other railroad, playing a vital role in interchanging freight traffic between the nation’s railways. Most significantly, it gave C.N. a bypass around Chicago, saving days of delay in Chicago’s clogged railroad yards.

Locally, Canadian National owns the former Illinois Central from Chicago to Sioux City and Council Bluffs, passing through Iowa Falls, Webster City, and Fort Dodge in the process. It has invested steadily in improved track, signaling, train control systems, locomotives and freight cars, and in so doing, upgraded the speed and reliability of its service to customers.

Van Diest Supply Co., on Webster City’s west side, is one of C.N.’s major customers.

According to Dustin Elliott, director of facilities for Van Diest Supply, the firm shipped or received a combined total of about 700 rail cars in 2023.

If this seems a small number, remember a modern freight car can easily weigh a quarter million pounds when fully loaded. Van Diest Supply gets a steady stream of raw materials via C.N., with most originating in Michigan, Louisiana or Florida. The company has a fleet of 70 modern tank cars that operate on a continuous basis from these suppliers to ensure the Webster City manufacturer never runs short.

In 2013, Van Diest increased the track capacity at its plant from nine to 70 cars.

“That’s when we began relying more on rail service,” Elliott said.

In addition to its Webster City operation, C.N. delivers carloads of fertilizer to Van Diest agronomy centers in Blairsburg and Duncombe. Van Diest itself doesn’t make fertilizer, but sells it to customers through its agronomy centers, as a matter of convenience.

Elliott called C.N. “reliable,” and couldn’t think of specific changes or improvements he’d make to the existing service. When asked if the railroad being owned by a Canadian company made any difference, he said, “No.”

Iowa’s Canadian-owned railways are of prime importance to Iowa industries that ship their products by rail, including grain, ethanol, fertilizer and pesticide producers. Canada is the largest producer of potash in the world, and its producers now have single-line rail access to more Iowa cities than ever before, meaning faster transit times and less likelihood shipments will be delayed. Potash is a key ingredient in fertilizer. Today, Canadian Pacific and Canadian National control an estimated 35% of class I railroad main line routes in Iowa.

Not everybody is celebrating the first birthday of the merged CPKC railway. After decades of neglect, Davenport has spent millions to build a string of parks along the riverfront and link them together with the 11.3-mile-long Mississippi River Trail. For almost its entire distance, the CPKC main line closely parallels the trail. If, as some analysts predict, train traffic triples through Davenport, heavy, slow-moving freight trains will be the constant companions of pedestrians, bicyclists and those out to enjoy the atmosphere of the riverfront.

City councils in Davenport and Bettendorf agreed not to oppose the rail merger, in exchange for cash settlements. Canadian Pacific paid Davenport $10 million, while Bettendorf and Muscatine each got $3 million. Davenport plans to use its cash to create “quiet zones” where trains will be prohibited from using horns, something required by federal law, unless crossings are upgraded to provide better protection for motorists and pedestrians.

According to the U.S. Federal Railroad Administration, protecting a street crossing with flashing lights and gates costs anywhere from $150,000 to $250,000, and can reduce railway/highway collisions by up to 42%. Flashing lights with four quadrant gates, which make crossing tracks while gates are down impossible for vehicles, costs $250,000 to $500,000, and can mitigate up to 82% of likely accidents. The ultimate treatment — separating roads and railroad tracks with viaducts — typically costs between $5 million and $40 million.

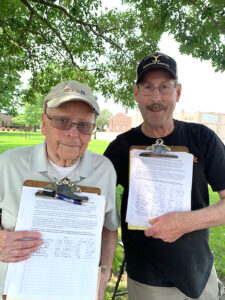

Members of the Brotherhood of Maintenance of Way Employees of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters used the special train’s arrival in Davenport in May to demand annual sick leave benefits for its members working for CPKC in Iowa. The union represents 28,000 track workers on railroads across the U.S. Called an “informational picket” by the union, they said they hoped to be noticed by railroad officials and the public as a way to start new negotiations. Other railroad workers and railroad unions have gained sick leave benefits in recent years, and the railway stressed that in its last contract the union’s members negotiated better wages and insurance rather than the sick leave they’re now seeking.